Click here for a PDF of the subject document, Col. Macleod's Dec. 27, 1874 letter.

Article by Laura Kirbyson

Laura holds a degree in Anthropology from the University of Manitoba, as well as a Public Learning Certificate in Genealogical Studies through St. Michael’s College, the University of Toronto. She has worked for many years as an historical and genealogical researcher, authoring reports and articles. Laura, with her husband, operates a small goat farm in Central Alberta. She has written books based on their experience raising goats and about moving to the country starting with nothing but a patch of land.

North-West Mounted Police Fort. Fort Macleod ca. 1875 NA-1406-197. Original sketch by William Winder. Public Domain. Glenbow Art Collection catalogue #57.33.21.

A Precarious Western Push

In August 1873, the Canadian Government issued Order in Council 1134. This established a police force meant to bring law, order and justice to the Prairies. The impact of this force, the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP), was felt almost immediately by the troops who participated and those who were living on the Prairies, which included the Indigenous populations. In the fall of 1874, after a grueling journey, the troops arrived in what is now Southern Alberta. It was a few months before Christmas and those who happened not to be sick, were tired, hungry, and unpaid.

The journey began with a recruiting advertisement asking for men between the ages of 20-35. The NWMP wanted individuals capable of riding and who would commit to three years of service. In return they would receive food, shelter, clothing and, upon completion of their service, a grant of 160 acres of land.[1] Just think of the opportunities! Promises of exploration and adventure all paid for by the Government and with the bonus of land ownership at the end. Over 300 men were hired. They would be led by Col. George Arthur French, a military man, and Lt. Col. James Farquharson Macleod, an educated man in a law practice who found passion in the militia.

In the early part of 1874, the troops set out and headed by train for Dufferin, Manitoba. From there, they would travel by horseback. The 3-month trip to their destination was grueling. Could any of them have been prepared for the trip based on their life experiences in relative comfort? This trip was approximately 900 miles, and that may, or may not have, included the extra travel for getting lost a couple of times.

The troops had experienced much crossing the Plains including vast herds of bison, terrible weather, bugs, and illness. Their beautiful horses were ill-suited for this work. Many did not survive the journey, although most of the troops did. As they crossed the prairies, imagine seeing those majestic bison covering the ground as far as you could see. Incredible and intimidating! Now imagine trying to drink the water after they’d all been through the ponds. From this and from sleeping in pre-existing camps that were bug infested,[2] it isn’t hard to understand the resulting illness. Headlines in Ottawa described the seemingly dire straits of the troops.[3]

Ottawa Citizen. April 7, 1875.

Arrival at Fort Macleod

It was not until later in 1874 that the troops reached their destination, now known as Fort Macleod, in southern Alberta. They arrived exhausted, hungry, in tatters, and without having been paid. There was nothing there for them, it was just a patch of land. On top of that, they were heading into a prairie winter.

The NWMP had headed west to reduce the abuses upon the Indigenous people by traders taking advantage of them, and the illicit sale of alcohol contributing to the abuse. They had not received any pay, were unable to receive mail, and supplies were limited. Their clothes were not sufficient for cold weather and their food consisted primarily of buffalo meat. As penalty for illegal practices, the traders’ supplies were confiscated by the NWMP. This turned out to be a boon for the troops as the supplies included clothing and food. Once the troops were established at Fort Macleod, further provisions started to arrive, and regular hot meals were available. That was a significant change from what they’d survived with during their march.[4] Things had started to look up into the beginning of December 1874.

The whole reason for the new police force was to make it safe for the inhabitants in the region. The goals were to establish law and order on the Prairies and to eliminate the illegal liquor trade with the Indigenous populations. They also wanted to develop ties with the Indigenous people.

Forming Connections

It is clear from many resources that there were interactions between the NWMP and the Indigenous people encountered along their journey. The NWMP had full time doctors on the march. Dr. Nevitt made side trips to “attend sick First Nations people”, as did the other NWMP doctor, Kittson. For the next few years, the NWMP doctors cared for the troops and the local populations, including the Indigenous (Alberta Medical Association). Relationships were made.

"Lieutenant-Colonel James F. Macleod, North-West Mounted Police Commissioner, 1876-1880.", [ca. 1876-1880], (CU195921) by Unknown. Courtesy of Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

The establishment of Fort Macleod began with stables for the horses. When you rely on your animals, your first duty is to see to their care. Fortunately, the men could also sleep in the stables while the fort was being built. The fort was named in honor of Lt Col. Macleod, one of the leaders of this new force. He seems to have been popular as a leader as the vote to name the fort after him was unanimous. Born in Scotland to a military father, Macleod immigrated to Upper Canada with his parents, beginning his education at Upper Canada College in 1845.[5] While in Ottawa, his family’s friendship with another family of local Ojibwa First Nations may have made Macleod an excellent choice for developing relationships with the Indigenous people on the Prairies. Col. Macleod is consistently described historically in positive terms both from the men he led and the Indigenous people with whom he developed respectful relationships. Not long after his arrival in the area, Col. Macleod was honored with the Blackfoot name, Stamix Otokan (Bulls’s Head).[6] From at least 1877 and to this day, the badge of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police includes a bison head. While the origins of the badge have been lost, it is possible that the inclusion of a bison head (Bull’s head?) might be related.

Once Fort Macleod was established, Col. Macleod met with different leaders, one of whom was Crowfoot, a very powerful and important chief of the Siksika (Blackfoot). The meeting took place on December 1st, 1874, at the new Fort.[7]

Painting of Crowfoot hanging at Fort Macleod ca. 2016. Photo by author.

The First Christmas at Fort Macleod

Going into the Christmas season would have been very, very different for the NWMP troops. Some had been born in the United Kingdom and others in Upper Canada, both far removed from the Canadian prairies. Christmas is generally full of families, traditions, and community celebrations. It’s a time where many of us tend to eat special foods, share gifts, and perhaps have a libation or two. All those options were severely curtailed, or completely unavailable, for the troops’ first Christmas at Fort Macleod. After their struggles, how difficult would it have been to think of celebrating?

The scene at Fort Macleod in December 1874 must have been so different from what the troops were used to. No decorations, no storefronts for window shopping or making gift purchases, no candy treats and no family. But they did have a new home and their clothing had improved, all in time for winter.

By Christmas, 1874, the mud-daubed log fort had been built, providing shelter for the horses, the men and the officers. Elk, deer and buffalo provided an abundant supply of meat, and the regimental tailors manufactured fur clothing from buffalo robes for winter weather.[8]

For many, Christmas is a magical time. A season of goodwill toward all mankind. That doesn’t just happen, it takes effort, and the NWMP troops made the effort. They had made the long march west and suffered on that journey but were starting to establish at least a few creature comforts. They could prepare a celebration.

One of the first full-time physicians in the West (Alberta Medical Association), Dr. Richard Barrington Nevitt wrote in a letter to his fiancée, Lizzie, about preparations for Christmas at the Fort. Two days before Christmas Eve, Nevitt attended a meeting “for the purpose of organizing the officers mess.” This was for the Christmas banquet. His December 24th description of what needed to be done in preparation for the 6 p.m. dinner is as follows:

Our Room had to be lined & cleaned – the stove had to be put up, the kitchen utensils, the table service & the rations from the various troops & many other little things.[9]

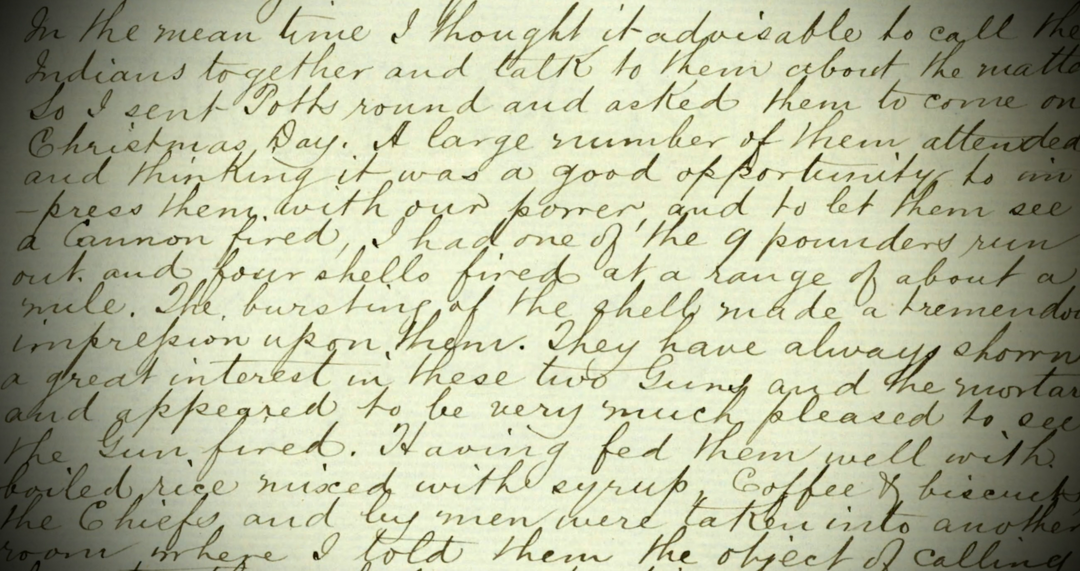

Nevitt also wrote that on Christmas Eve there “[was] going to be a great Pow-wow. All the Indian chiefs from far and near have been invited to come and… the place has been alive with Indians in gay & festive attire. They are to have a big feed & the power of our guns & mortars are to be demonstrated to them”.[10] According to Sergeant Frank Fitzpatrick, who participated in the demonstration, Sergeant Spicer took a shot at a lone dead tree across the valley. “He aimed carefully and fired. It was one shot in a hundred. He had cut the fork branch, and raised an enormous amount of earth”.[11] According to accounts, including that of Col. Macleod himself, the Indigenous observers were impressed.[12]

After the Christmas Eve demonstrations, that first Christmas was held in the Fort’s hall “blazoned with banners painted in vermilion on white cloth” and the food was a veritable feast for the men who’d had very little to eat during their march west, mostly tough bison. It included: “buffalo, venison, antelope, canned fruit, plum pudding, and tea,” as well as a turkey. One turkey, supplied by the IG Baker Trading Company, for 150 men. Not surprisingly, as a mandate of the force was to get rid of liquor, there was none for the troops. The officers, however, shared “a small jar of whiskey” at a private dinner afterwards.[13]

An Ottawa Citizen article described “Xmas [sic] Day on the Prairies”. From today’s perspective, it seems downright uncomfortable, but at the time and after the struggles, this was largesse.

[Christmas Day] was hailed with pleasure, as it brought “a holiday” with it! Many attempts were made at decorations on a limited scale, and to see the happy faces of the men at dinner, it would never be supposed that they had been months [emphasis in original] without a change of underclothing. …

After the usual toasts had been drank (in coffee) and responded to, though there was a little of the “soldiers comfort,” (old rye) [illegible] amongst some of the men, the Colonel [Macleod], in responding to his health made a long speech, completely winning back the hearts of the refractory ones.[14]

The Christmas meal was followed by a social event that included a dance. The NWMP interpreter, Jerry Potts, had invited the Indigenous women from a nearby camp to join in the festivities. Constable Cecil Denny was among the 1874 troops. He described “a grand dinner prepared by our chef and attended by all” and that the dance that followed included as their partners local Métis girls.[15]

One hundred and fifty men, new to the region and the existing community, made a start on creating new lives for themselves. While it began with an arduous journey fraught with terrible conditions, the year ended bringing together two vastly different people. The celebration would have meant so much to those who’d left behind family and friends, and so much going into an unknown future. While we can speculate on the NWMP troop’s perspective, one wonders what the local Indigenous people thought of this event.

Fort Macleod today.

Sources

[1] Glenbow Archives NA-2603-2. Description obtained from University of Toronto Libraries. Online, https://exhibits.library.utoronto.ca/items/show/2641

[2] Boundary Trail National Heritage Region, RCMP Heritage Series: Maunsell’s Story. Cited from, Maunsell, ex-Sub/Cst. EH Maunsell. RCMP Quarterly Winter. Online, https://www.bthr.ca/boundary-trail-archives/boundary-archives/. Accessed 20 December 2022.

[3] Ottawa Citizen. The Mounted Police. April 7, 1875. Column 3. Provided by Stephen Robbins, personal collection.

[4] Hollihan, Tony. The Mounties march west: the epic trek and early adventures of the Mounted Police. Edmonton: Folklore Pub. 2004. Online via Archive.org, page 206.

[5] Boundary Trail National Heritage Region, RCMP Heritage Series: Stamix Otokan. Cited from, Forrest, B. Commr. DO. The Nor’-West Farmer Vol. 45, No. 4 Fall 1980. Online, https://www.bthr.ca/boundary-trail-archives/boundary-archives/. Accessed 20 December 2022.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Hollihan, Tony. The Mounties march west: the epic trek and early adventures of the Mounted Police. Edmonton: Folklore Pub. 2004. Online via Archive.org, page 215.

[8] Boundary Trail National Heritage Region, RCMP Heritage Series: Stamix Otokan. Cited from, Forrest, B. Commr. DO. The Nor’-West Farmer Vol. 45, No. 4 Fall 1980. Online, https://www.bthr.ca/boundary-trail-archives/boundary-archives/. Accessed 20 December 2022.

[9] University of Calgary. Richard Barrington Nevitt fonds. M-893-4 Letters to Lizzie, 1874. Online, https://glenbow.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/m-893-4-transcriptions.pdf. December 24th Entry. Accessed 20 December 2022.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Dunn, Jack. The first Christmas at Fort Macleod and Fort Edmonton. Extracts from Sabretache. December Extra #2 2020, page 2. Provided by Stephen Robbins, personal collection.

[12] Reports of Asst Comm JF MacLeod from Fort MacLeod. Library and Archives Canada. RG18, Volume 4, File 115-75. From the collection of Dave Senger.

[13] Dunn, Jack. The first Christmas at Fort Macleod and Fort Edmonton. Extracts from Sabretache. December Extra #2 2020, Page 2. Provided by Stephen Robbins, personal collection.

[14] Ottawa Citizen. The Mounted Police. April 7, 1875. Column 3. Provided by Stephen Robbins, personal collection.

[15] Denny, Cecil. The Law Marches West. Denny Publishing Ltd. Gloucestershire: 2000, page 52.